Angela McCarthy, Professor of Scottish and Irish History at the University of Otago, looks at the memorialisation of James Taylor, ‘father of the Ceylon tea enterprise’, ahead of the 150th anniversary of Ceylon tea in 2017.

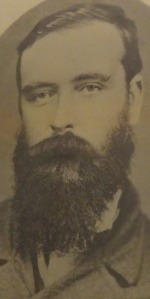

Scotsman James Taylor is renowned in Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon) as the ‘father of the Ceylon tea enterprise’ because his experiments during the 1860s led to the first successful commercially cultivated crop of the famous beverage. Publicly celebrated in Ceylon in 1891 for his achievements, he received a silver tea service. The following year, however, Taylor died in disgrace following dismissal from the estate he had managed for 40 years. His friends and fellow planters took to the press to hotly dispute accusations from his employer that Taylor was lethargic. That press coverage also documents developments surrounding Taylor’s burial and memorialisation.

On Tuesday 3 May 1892, a day after his death, Taylor was taken from the Loolecondera estate where he lived and worked for burial at the Mahaiyawa cemetery near Kandy. Two gangs of 12 estate workers reputedly carried Taylor’s body to his final resting place. They alternated every four miles during the 18 mile journey. Among neighbours and friends who attended the ceremony were C.E. Bonner, W.J. Scott, Stopford Sackville, Alexander Philip, and several others who had subscribed to Taylor’s silver tea service. Revd Watt read the funeral service.

Such was the esteem with which Taylor was held among the planting community that W.H. Walters of Gonavy suggested the erection of a granite slab and headstone on Taylor’s grave together with an inscription recognising Taylor’s contributions to both the tea and cinchona enterprises in Ceylon.[1] A fund was established and among the 52 contributors were Taylor’s sister Margaret Nairn in Scotland and Sir Thomas Lipton (another Scotsman whose name is most famously linked to Ceylon tea). Of a total sum of 1,135 rupees and 86 cents, Margaret donated the largest amount (410 rupees and 26 cents). This was likely due to her being a beneficiary of Taylor’s will.

The memorial fund was used to obtain a tombstone (£44.1.0) and ship it from the UK, pay landing charges, rail, cart and ‘coolie’ hire, erect the headstone at the cemetery, acquire chains and pillars to place around the grave and build the foundations, and provide photographs of Taylor and the grave and postage to send the images to Scotland. The press reported that ‘At one end of the marble-enclosed grave, rises a tasteful pedestal surmounted by a granite and flower-carved cross’.[2] Its granite construction reflects Taylor’s origins in the northeast of Scotland while the vegetation seems to depict the passion flower symbolising Christ’s passion. At the centre of the cross can be seen the IHS symbol, also representing Christ. Absent, however, is any reference to Taylor’s origins in Scotland. Instead, his contribution to Ceylon’s economy is to the fore. Crucially, however, his gravestone did not simply showcase secular respectability and affection but demonstrated spiritual concerns, presumably those of his sister.[3]

In 1997 a group of Japanese tea dignitaries added an additional plaque to the grave to commemorate the 110th [sic] anniversary of Ceylon tea. It was presumably on this visit that the delegation is said to have cracked open a miniature bottle of whisky on Taylor’s grave. More recently, tea trees have been planted beside the grave further testifying to Taylor’s importance to the country’s tea economy. As well as his gravesite, Taylor is commemorated in Sri Lanka in diverse ways including tea tins, sculptures, and exhibits at the Ceylon Tea Museum. Perhaps most striking of all is a 16 foot bust which stands at the entrance to the Mlesna tea castle at Talawakelle, a mock Scottish baronial castle which opened in 2008.

By contrast with his memorialisation in Sri Lanka, James Taylor is not commemorated in the cemetery at Auchenblae in Scotland where his father and mother are buried. This is striking as his sister Margaret did not erect a plaque to parents Michael and Margaret Taylor until 1896, several years after Taylor died. It is even more puzzling given the reference on her stepmother’s headstone in the same cemetery to half-brother William’s death in India in 1894. Nevertheless, James Taylor is remembered on a blue heritage plaque on his childhood home at Mosspark while National Museums Scotland holds in storage his silver tea service.

Unlike other headstones of British migrants in Sri Lanka (to feature in a subsequent blog posting), Taylor’s gravestone does not contain explicit reference to his birthplace in Scotland. Rather, his origins are indirectly discerned through the use of granite. It is, however, Taylor’s professional identity in his adopted homeland and his influence on Sri Lanka’s economy that is commemorated. This is likely due to the role of the planting community rather than immediate kin connections in proposing the text on his headstone. With the 150th anniversary of the Ceylon tea enterprise forthcoming in 2017, Taylor’s grave and associated memorials in Sri Lanka and Scotland will likely attract enhanced interest.

Angela McCarthy is Professor of Scottish and Irish History at the University of Otago and is Academic Advisor and Research Consultant to the British diaspora component, ‘Identity, meaning and memorialisation in the British Diaspora’, of the ‘Remember Me: The Changing Face of Memorialisation’ project. She is currently writing a biography of James Taylor.

[1] Overland Times of Ceylon, 23 May 1892, p.678. The text Walters proposed was: ‘To the memory of James Taylor of Loolecondura, the originator of the tea and cinchona enterprise, in Ceylon, who died May 2nd, 1892. This stone is erected by his friends in token of their high respect and esteem’. The final inscription deviated slightly from Walters’ proposed text as the photograph of Taylor’s grave shows.

[2] Overland Ceylon Observer, 25 November 1893, p.1323.

[3] Julie-Marie Strange, Death, Grief and Poverty in Britain, 1870-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 100-1.

One Comment Add yours