Remember Me researcher Dr Yvonne Inall, who is working on our Deep Time study explores a rare Iron Age burial ritual, unique to East Yorkshire.

In the summer of 2015 I received an incredible invitation, one of those not to be refused. Archaeologists from MAP Archaeology Ltd. working at Pocklington, in rural East Yorkshire found an astonishing burial of a young man who had been buried with weapons, including multiple spearheads. As someone then about to complete a PhD on the topic, I could barely contain my excitement – I was going to see a ‘speared corpse’ burial in situ!

But what is a ‘speared corpse’? And why was I so excited?

I first heard of the phenomenon in 2011, not long after I had finished my Masters degree at the University of Sydney. I was at an international conference, presenting my work on Italian Iron Age spears and another delegate, from the University of Hull, presented a paper about Iron Age East Yorkshire. He spoke briefly of a burial rite, seemingly unique to the region, in which spears had been thrown into the open grave as part of the funeral. Sometimes the spears appear to have pierced the body of the deceased person. It was such an extraordinary and dramatic practice that it captured my imagination. So much so, that I upped sticks and moved from Australia to East Yorkshire and re-focussed my research from the Iron Age Mediterranean to examine the spears and burial practices of Iron Age Britain.

I have since learned that the ‘speared-corpse’ burials of the British Iron Age (conventionally dated between 800BC to 43AD) were actually extremely rare. Of the many hundreds of Iron Age burials excavated across Britain since the nineteenth century fewer than 25 individuals were subjected to this rite, all of them situated in East Yorkshire. Given the exceptional rarity of ‘speared corpse’ burials I did not expect that another would ever be discovered. Indeed, the last time such a burial had come to light was in the 1980s at Wetwang, where John Dent excavated an extensive Iron Age cemetery. Just one of 446 Iron Age burials at Wetwang was a ‘speared-corpse’ burial. So the news of the new discovery at Pocklington represented a spectacular find of both national and international importance. The opportunity to be one of the first people to see the burial, and the prospect of examining the spearheads were, for me, the stuff archaeological dreams are made of!

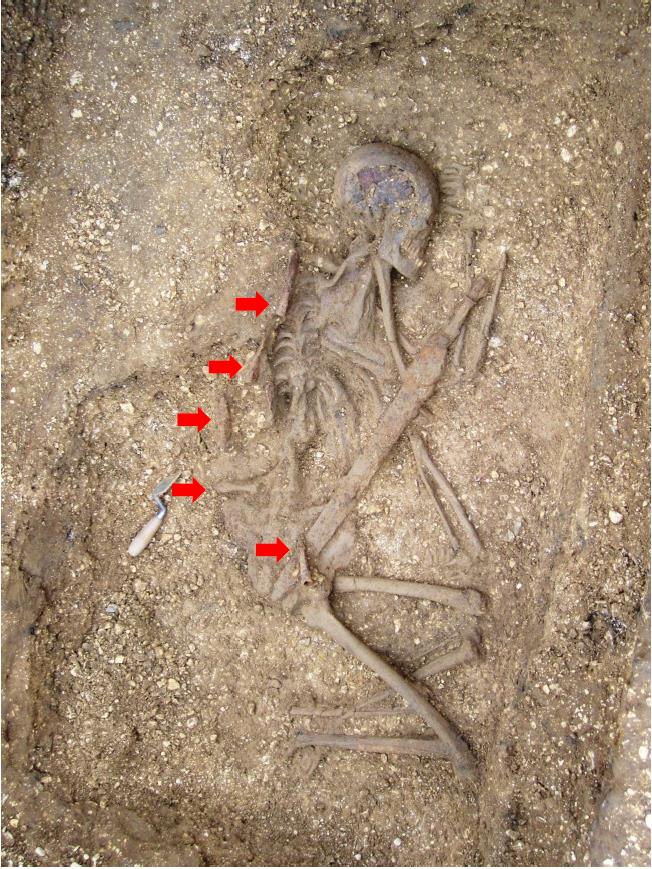

MAP Archaeology’s careful excavation of the site enables us to reconstruct some of the funeral practice for this individual. The burial was that of a young man, around 17-23 years of age, what would have been considered the prime ‘fighting age’ in Iron Age society. His body was carefully laid on his left side, in a crouched position, with his left knee drawn up level with his hip. A wooden box in the base of the grave may have formed a coffin for him. An iron sword in a wooden scabbard was carefully placed over his torso, with the hilt close to his right shoulder. Five iron spearheads and an iron ferrule (spear-butt or counter-point) were also included in the burial. However, despite the ‘speared-corpse’ moniker most of these weapons do not appear to have been thrown into the grave. Four of the spearheads had been carefully placed in a row along his spine. Traces of wood in their sockets suggest the shafts had been broken before they were deposited. The iron ferrule and one of the spearheads lay at an angle, close to the hip. It is possible that these were thrown into the burial, although these too could have been carefully placed. Again, the spear shafts appear to have been broken before the grave was filled in.

This placement is consistent with some of the other ‘speared-corpse’ burials. There is clear variation in practice with some spearheads carefully placed like those at Pocklington, while others were scattered around the base of the grave. Sometimes the spearheads were found in the soil used to fill in the open grave, with their tips pointing downward, demonstrating that they had been thrown in when the grave had been partially filled in. Their discovery in these layers of grave filling soil by Ian Stead during his excavations at Rudston and Burton Fleming in the 1960s and 1970s confirmed that the spears formed part of the funerary ritual and were not the cause of death, as had previously been assumed. My own research into British Iron Age spears has revealed that the spears used in ‘speared-corpse’ burials were all forms designed to function as throwing spears, lending further support to the interpretation that many of the spears were thrown into graves.

Following the realisation that the spears were used as part of the funeral rite the next logical question was: why? We can speculate about the underlying motive for the ritual with reference to the practices of other cultures. Many cultures feature ‘ghost-killing’ rituals, where a person thought to have died a ‘bad death’, and who presented a danger to the living would be subjected to specific rites designed to prevent them from rising from the grave. These kinds of rites could include face-down burial or mutilation of the corpse, sometimes using weapons. Such burials are usually located away from other burials, and other funerary rites and monuments one would expect to see are not provided. Clearly this was not the case for ‘speared-corpse’ burials. At Pocklington, and in other examples, the burial is within the communal cemetery and all of the usual funeral rites are enacted. The ‘speared-corpse’ burial at Wetwang, for example (also the burial of a young man), was one of the richest burials in the cemetery, equipped with a sword and a ‘chariot’. So, we can probably rule out an attempt to stop this young man at Pocklington rising from his grave. The rite may have been to ensure his was a ‘warrior’s death’, enacted to safeguard his passage to the afterlife. Alternatively, the rite may represent his fellow warriors offering a form of martial salute, like the 21 gun salute performed at military funerals today.

The burial of the young man at Pocklington was marked by a visible monument in the form of a burial mound surrounded by a square ditch. His was just one of numerous barrows stretching across the landscape at Pocklington and other Iron Age sites in the locality. The practice of creating burial mounds within square-ditched enclosures was a distinctive feature of Iron Age East Yorkshire. The so-called Arras Culture is named after one of the first Iron Age cemeteries in East Yorkshire to be excavated, at Arras Farm on the Yorkshire Wolds. That cemetery is now intersected by the A1079 and the burial mounds have long disappeared under the plough. At certain times of year the square ditches appear as crop marks in the field, offering a glimpse of this past ancestral landscape. Since the nineteenth century Arras Culture burials have been recorded by field survey and aerial photography at hundreds of sites across East Yorkshire. The excavations at Pocklington, using the latest excavation and sampling techniques present an opportunity to examine the Arras Culture in greater detail. For my own small part, I am relishing the opportunity to work closely on the spearheads and sword, contributing to the formal excavation report.

Dr Yvonne Inall was recently awarded a PhD in History from the University of Hull, undertaking an archaeological examination the role of spearheads in Iron Age Britain. As part of her doctoral thesis Yvonne conducted a review of British Iron Age burial practices, with a particular focus on martial burials. She is now assisting Professor Malcolm Lillie with the long durée component of the Remember Me Project: Deep in Time: Meaning and Mnemonic in Archaeological and Diaspora Studies of Death.

9 Comments Add yours